The artifacts of our lives

A story about loss and what we might find in other people's belongings

Hi friend,

I had planned to share a different post today. However, I’ve been dealing with an unexpected health issue this week, which has left me in near-constant pain. I won’t go into all the details, but it’s been reminiscent of what life was like after my car accident in 2013.

Anyway, while I’m off chatting with doctors and tending to my body, I am leaving you in the hands of our first guest writer. ❤️

Maddie is a former financial planner who helps others navigate (and embrace!) life's profound uncertainty through her writing at Your Five-Year Plan. She writes, quite literally, about what you might do when your plans go up in flames. It feels appropriate that I can share her story this week, so I can be offline…

This isn’t a story about plans going up in flames. It’s a story about (a huge) loss, and going through people’s belongings, and what we might discover in the process. She pitched it shortly after I learned my grandma had unexpectedly passed away in August… and it was an immediate yes from me.

Guest posts don’t always get as much traction as “regular” posts. We want to hear from our people. We are short on time. And we don’t have relationships with these other voices yet. So why give our limited time to people we don’t know? I sit with these same questions, sometimes as a reader. But here is what I know…

You have a relationship with me. And I am committed to publishing guest posts I believe you will enjoy. Posts written by introspective, thoughtful, and curious humans. Maddie is certainly one of those. Working together on this was such a meaningful experience, and showed me I’m on the right path with Explore Within.

I am so grateful she’s offered to share her story with us.

Over to you, Maddie.

xx Cait

UPDATE on October 7, 2023: Turns out, some people loved this guest post! So much so that Maddie’s post was recommended by a reader and featured on Substack Reads this week! (Which is why we got to add the cute little “featured publication” image to it!) Thank you for reading and supporting her work, and thank you to for helping more people find it.

GO MADDIE! 🥳

The artifacts of our lives

by Maddie Burton

When my mom died in February, I learned that the heavy task of grieving is made infinitely more complicated by stuff.

But I already knew there was a tricky relationship between our tangible belongings and the hauntingly intangible aspects of our legacies. I’d seen the tension between holding on and letting go build and release many times over.

In December of 2000, we moved into my mom’s new townhouse to find it full of a dead person’s possessions.

Everything was preserved exactly as Sandra, the previous owner, had left it: her furniture, the hall closet stuffed full of baking equipment in original packaging, the mirrors on every surface. Even—as I would learn much later—the thirty thousand dollars in cash that my mom found squirreled away in the bathroom vanities.

Like any fourteen-year-old, I focused on the odd nature of some remaining artifacts, like the tooth-shaped flowerpot. (Sandra had been a dentist, so on some level it made sense—but on another level, well, it was a tooth flowerpot.)

We discarded the flowerpot, but my mom kept Sandra’s furniture for almost twenty years. Money was, all of a sudden, meaningfully scarcer after the post-divorce division of one household into two.

For a fleeting moment, though, I wondered why someone else hadn’t taken Sandra’s things: the furniture, the rubber-banded rolls of cash, the tooth flowerpot.

In 2017, when my grandparents passed away within weeks of each other, my mom and her siblings sifted through their belongings. I’d receive periodic calls from my mom, who wanted to save everything.

“Do you need a set of china, or extra wine glasses?” she offered hopefully. I reminded her that I lived in a one-bedroom already packed to the gills.

The next time we met for dinner, she pulled out a surprise: something crab-shaped made of pewter.

“It’s a chip-and-dip,” she exclaimed, “for when you have people over!”

I’d already declined countless offers for hand-me-down heirlooms, so I gracefully accepted the chip-and-dip. I’d donate it later, quietly, to save her the heartbreak of doing so herself.

The next time I came home, Sandra’s furniture had been replaced by the entirety of my grandparents’ living room: the slipcovered sofa and easy chairs, the art collection they’d pieced together over a lifetime of joint world travels, the dining table my mom took pains to refinish.

She couldn’t bear to let go of her parents, so she kept them in whatever form she could.

My mom’s second battle with cancer gave me whiplash: diagnosed last autumn, in hospice by New Year’s, gone by Valentine’s Day. Our family went from cheerleaders for trying immunotherapy to managing her end-of-life care with nauseating speed.

Others reassured me that clearing her house could be relatively simple, if not easy. Step one: walk through each room and identify what to keep. Step two: hire someone to take the rest away, presumably to the landfill.

But I felt attached to everything, even the perishable goods: the wilting bouquets she’d bought the previous week, the leftovers in the fridge we’d just shared. I wanted to preserve each petal. I resented that everything had an expiration date.

So I took a different path forward.

Alongside neighbors, friends, and our hired guardian angel Carrie, my brother and I went through everything in her 2,300-square-foot townhouse. Like Marie Kondo instructs, I needed to touch each item, thank it, appreciate what it had meant to her.

We resolved to donate as much as possible, rather than sentence everything to the landfill. My mom’s possessions were precious to her, and their legacy could live on, beautifying someone else’s living room.

Carrie was as efficient as she was empathetic, uttering “that’s so tender!” whenever we came across a poignant memento. It was a phrase I’d hear frequently over the next nine days because absolutely everything was tender. (Except, of course, for the things that weren’t, like the vintage East German apple corer my brother found at the back of a kitchen cabinet.)

And treasures dotted the trash. I flipped through a seemingly-new box of one hundred manila folders, only to find six 5x7” hand-painted works of Japanese art distributed randomly among them. It was as if my mom was playing a cosmic joke on us from—well, wherever she was now.

The wall of floor-to-ceiling bookshelves held her most prized possessions. We flipped through each book in her collection, removing hundreds of notes she’d scribbled on index cards and tucked between pages. One reminder said “donate self-help books to women’s shelter” as we were doing just that.

Another sign that we were on the right track.

We pared down the house until it held only its most beautiful items. My mom often accumulated, but rarely decumulated; I wished she could’ve seen how, like a clay sculpture, her home became more itself by way of subtraction.

Despite our massive decumulation efforts, we still left with thirty boxes of keepsakes. I brought them into my own home to contend with.

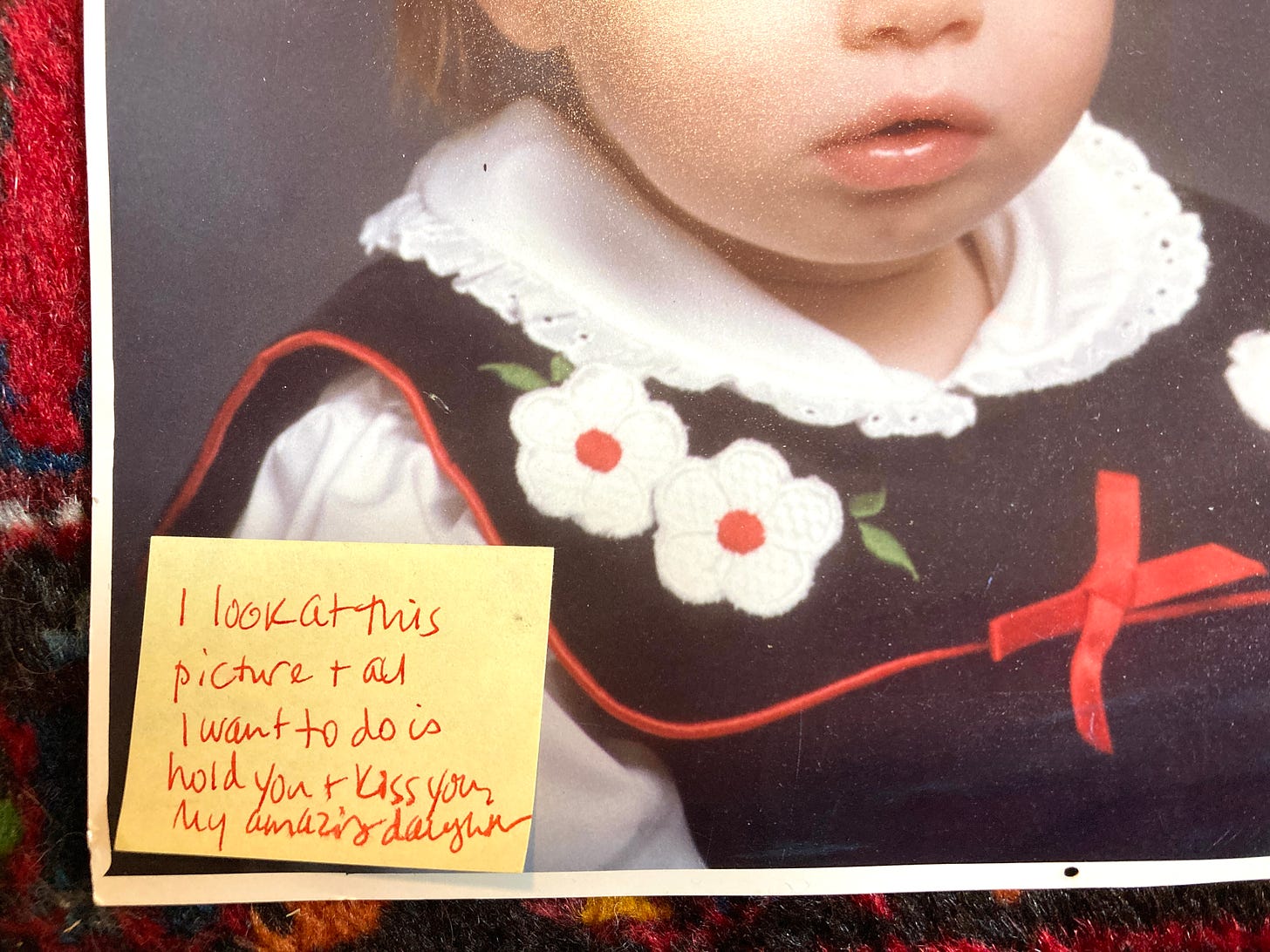

As I began sorting through the childhood mementos and pieces of family history, I wanted to cling to each item—to grasp everything intangible it represented, to turn the clock back. Every piece of macaroni art transported me to a carefree moment when I thought my mom would live forever.

But the clock only spins one way.

In my mom’s final days, I found comfort in a poem by Kahlil Gibran called “The River Cannot Go Back.” He writes about a river afraid to enter the vastness of the sea. Knowing the impossibility of reversing course, he offers these words of solace:

“The river needs to take the risk

of entering the ocean

because only then will fear disappear,

because that’s where the river will know

it’s not about disappearing into the ocean,

but of becoming the ocean.”

An hour after she died, gale-force winds started blowing. Shops and restaurants locked their doors to keep them from whipping open and shut, again and again. When I left the hospital, I struggled just to stay vertical, to open my car door.

My mom was a force of nature. Her emotions were big, her unyielding love and generosity even bigger. But, like all of us, she was bound by the limitations of her human form. She battled alcohol dependency, then depression, then the side effects of cancer treatments that only worked for so long.

The wind felt like confirmation that she’d been unleashed, that on some different plane she was now unstoppable.

I’d spent years denying that I inherited her force-of-nature tendencies, that same gale-force wind. I cataloged our differences: where my mom was as expansively beautiful and messy as her house, I kept myself as prim and orderly as mine.

One of these boxes contains her toucan earrings, her faux-fur capelet, her floral-print velvet cardigans. Reader: I wear neutrals.

For a long time, I thought of life—not just drawers and closets—as something that could, and should, be tidied. Then, my marriage ended. My mom died. I got laid off. Certainty and tidy narratives began eluding me.

Each blow was an inflection point: do I step back or step up? Do I fade into the beige-and-taupe background that’s comfortable for me? Or do I start following my mom’s playbook, slip on a pair of leopard-print heels, and stride forward?

Looking over the sea of boxes in my living room, it would be easy to see them as anchors weighing me down. But they just might be invitations: to discover parts of her I’d like to try on for size, by sifting through the artifacts of her life.

Maybe it’s time to embody her boldness.

Maybe it’s time to become my mother’s daughter.

A few other posts of Maddie’s I think you might enjoy: Don’t make plans, give gifts | Bank your memories | A declaration of interdependence

Oh wow, this was really beautiful. Thank you so much for sharing.

A great post and so meaningful for me. My mother passed late last year and for a while I lived in her house, surrounded by her things. It's sad to think of the stuff we leave behind... But I was inspired by your lovely words: "Looking over the sea of boxes in my living room, it would be easy to see them as anchors weighing me down. But they just might be invitations: to discover parts of her I’d like to try on for size, by sifting through the artifacts of her life." Thank you!